The more recent news with Tim Schafer and the rest of the folks at Double Fine is a Full Throttle remaster and the Psychonauts sequel they’ve crowdfunded. While these are both very awesome things, let’s not let that overshadow the truly important, groundbreaking, earthshaking game that Double Fine released last year: Day of the Tentacle.

Okay, so it’s just a remaster of one of Schafer (and Dave Grossman)’s older Lucasarts titles so maybe it already finished up all its earthshaking when it was originally released in 1993. But perhaps you made a huge mistake and missed the game back then. Heck, some of you might not have even been alive for the original release, which is kind of a valid excuse, I guess.

But even if you did play it back then, this is an adventure game well worth revisiting because it’s one of the only well-designed adventure games in existence. With the sharp increase in fans-turned-indie-developers as well as the popularity of Telltale’s episodic titles, the adventure game genre has experienced a recent resurgence. It’s too bad so many of the games are poorly designed.

In fairness, it’s understandable that many new adventure games don’t get it right. They’re built upon the blueprint of classic adventure gaming, a rather rocky foundation, indeed. Super Mario Bros., the progenitor of platformers, has a very limited number of ways for the player to affect the game world (jump on or run into things) and is therefore easier to copy and build upon. Adventure games, however, were saddled with an identity crisis from the start, defined by little more than the broad concept of allowing the player to influence and/or further the game’s story. But this covers pretty much any game that has even the bare bones of a story. I mean, by this definition, you could argue Mario is an adventure game too! It’s got a story about a princess being forever in another castle and she’ll never get out of there unless you keep heading to the right.

I imagine most people would suggest the difference is that, in an adventure game, the story is progressed through puzzle-solving, but this definition, too, is flimsy. Not even addressing the fact that so many modern gaming genres (platformers included) now incorporate puzzles into their gameplay, the adventure games of old were a grab-bag of all sorts of nonsense in the first place.

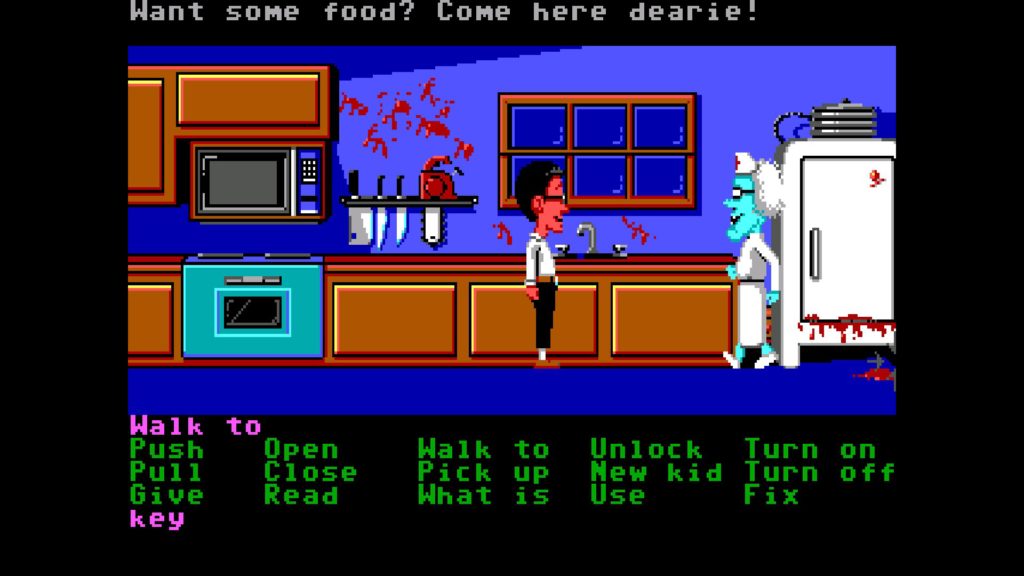

From the very first Space Quest (released in 1986) on, classic developer Sierra On-Line started chucking the occasional action sequence into their games. And one could argue their titles always had an aura of action gaming to them considering that in the very first King’s Quest (1983) you frequently had to pilot your character with deft precision, lest you send him tumbling off a cliff or down a tree or into a moat on literally the first screen of the game. On the Lucasarts (then Lucasfilm) side, Maniac Mansion (1987) has an arguably action-game moment where you have to wander into the kitchen to attract Nurse Edna’s attention and then quickly click your way out before she catches you.

But let’s say the action elements in adventure games are a misstep away from the puzzling that should define them. In that case the question remains: what the hell constitutes a puzzle in adventure gaming?

Typically, an adventure game character possesses the ability to amass a vast inventory and puzzles are solved by using inventory objects in one of three ways. You can use them on other objects in the environment (e.g., using a rubber chicken with a pulley in the middle on a rope stretched across a chasm lets you ride the rope like a zipline). You can give objects to other characters (give a tailor a golden needle in exchange for a fancy cloak). Or you can combine objects with other objects in your inventory to make a completely new object (a stick and a string works as a fishing line), which you’ll then need to use on something else altogether.

Maniac Mansion (1987)

But there’s so much more that has nothing to do with your inventory whatsoever! Sometimes you can solve a puzzle through conversation with another character (this is how you defeat the villain and solve the final puzzle of Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis). Sometimes you get a close-up of the inner-workings of a contraption and have to flip switches and shift around doodads to get it working (the entirety of Myst). Some puzzles are based on timing (in Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge, Guybrush must spit when the wind blows to win a spitting contest). Some puzzles are music-oriented (The Neverhood makes you recreate a tune you heard in one area to open a door in another). Returning to the first King’s Quest, there’s a notorious puzzle that might be classed as code-breaking where you have to guess Rumpelstiltskin’s name, but in this case it happens to be based on a backwards alphabet (the correct answer is, duh, Ifnkovhgroghprm).

The simple truth of it is that adventure games straight-up never figured out what a puzzle should be. And I need to digress here to note that this point, put so succinctly, was lifted from this insightful video analysis of Sierra adventure games. In fact, these videos really helped me frame my understanding of adventure gaming’s problems in general and they’re definitely worth checking out.

To continue, it’s this problem of not knowing what a puzzle is—and, by extension, what sort of challenge an adventure game should offer—that has been passed down to modern adventure gaming. Current developers have more conventions to build upon, but regularly do little more than ape their influences, so their games therefore still suffer from inconsistent, unclear logic (see 2D adventure Violett, painfully-obtuse mobile 3D game Hiversaires, or much of developer Daedalic Entertainment’s output).

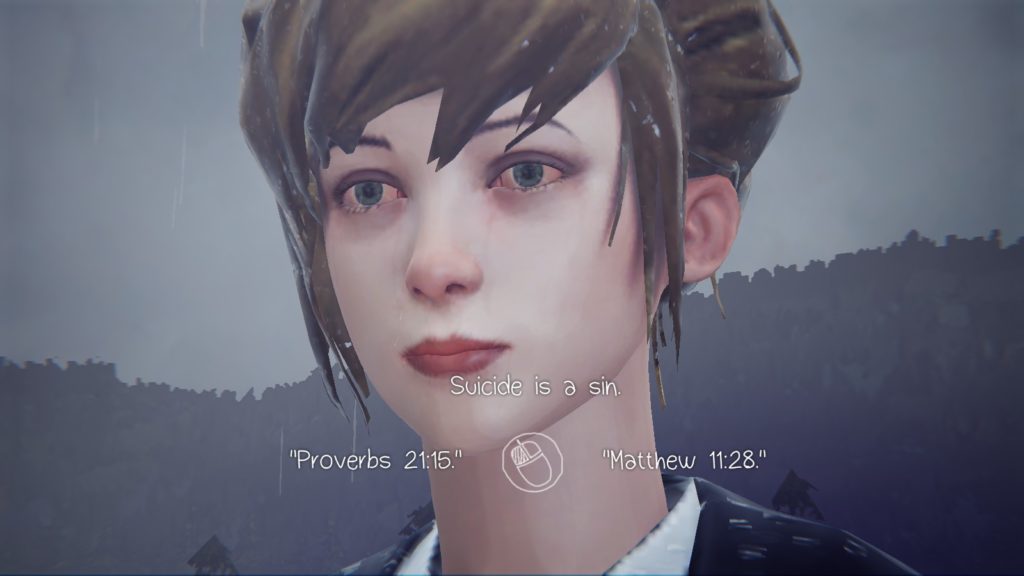

An annoying number of new titles have clung to the conversational aspect of adventure games—probably the most boring aspect—making selecting dialogue options the primary focus. Indie games Primordia and the upcoming Octopus City Blues are burdened with an overwhelming amount of chatter (though the latter title still has time to change). Or there are the no-longer-new-but-not-old-enough-to-be-classic The Longest Journey and Dreamfall (games I still love, but, yikes, nobody ever shuts up). Most notably, are games by Telltale, starting with The Walking Dead, which have all but turned their back on the puzzle-solving aspect of the adventure genre, becoming little more than dialogue-option-picking, interpersonal communication simulators (and have inspired further such games, like the wildly overrated Life is Strange).

The Walking Dead

This direction for adventure gaming is indicative of the overall simplification of the genre. It’s worth noting that, over time, the manner in which adventure games accepted player input was completely overhauled. At the start, adventure gaming was fully text-based and players typed in commands to make their character perform actions (e.g., “GET BRIDLE,” “PUT BRIDLE ON HORSE,” “MOUNT HORSE”). This gradually transitioned into mouse-driven gameplay (giving the genre the alternate title of “point-and-click games”) and various elements were pared down to reduce complexity and confusion, eventually resulting in the general standard of today: left-click to perform an action, right-click to look at something (though sometimes even the right-click is done away with).

Though I think the move to point-and-click was an overall good one, it still feels like the beginnings of the adventure genre feeling ashamed of itself. This is a genre afflicted with massive overcorrection, apologizing for what it did to players in the past with that awful Rumpelstiltskin riddle or the monkey wrench puzzle from Monkey Island 2 that was unfair before you even take into account that people outside of North America don’t call them “monkey wrenches.” Games like the Syberia series (which for some reason is getting a second sequel soon) heralded a new wave of adventure gaming afraid to annoy you, touting simple, “realistic” puzzles that follow naturally and don’t hurt your head. It’s more about appreciating the story than figuring out crazy crap anyway, right?

Well, sort of. The story is a massive aspect—perhaps the main aspect—of these games that draws people to them. But I believe what truly makes them work the rare times that they do and what so few of them got right and continue to not get right is an intrinsic relationship between puzzles and story (again, another point I’m lifting almost wholesale from this aforementioned video series).

Yes, I know, this is still a vague definition of adventure gaming. I can’t do much about that as I don’t possess the skills to define a genre that, in over three decades, hasn’t managed to properly define itself. But, luckily, I have examples from the best-designed adventure game ever, Day of the Tentacle, to help illustrate what I mean.

SPOILER ALERT: I have done my best to discuss the puzzles in this game as non-specifically as possible, but this is a deep analysis of the game design so some spoiling is unavoidable. If you haven’t played Day of the Tentacle, you might want to do that first (the remastered version is now available on most platforms) as I would never want to rob anyone the joy of figuring out the puzzles in this uniquely brilliant title.

THE PUZZLES ARE THE STORY

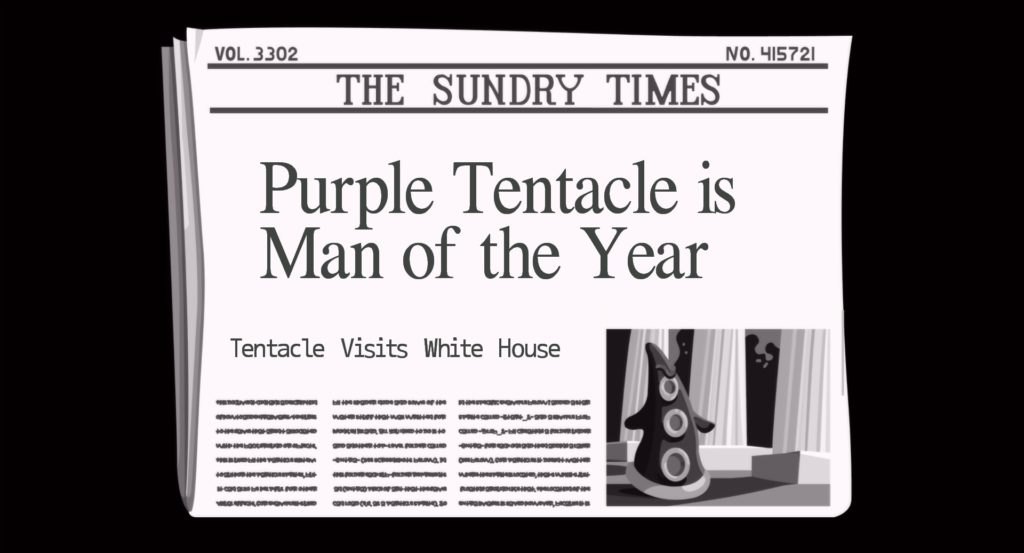

DOTT understands, better than any other adventure game before or since, the symbiosis of puzzles and story. The plot concerns a sentient mutant tentacle named Purple Tentacle who drinks some toxic sludge from a polluted stream, causing him to grow little arms along with a desire to take over the world. The sludge is pumped out by a machine, the Sludge-O-Matic, so the solution to saving the world is simple enough: turn the machine off. Unfortunately, Purple Tentacle already drank the sludge, so the machine needs to be turned off yesterday before he gets the chance. So, time travel it is then.

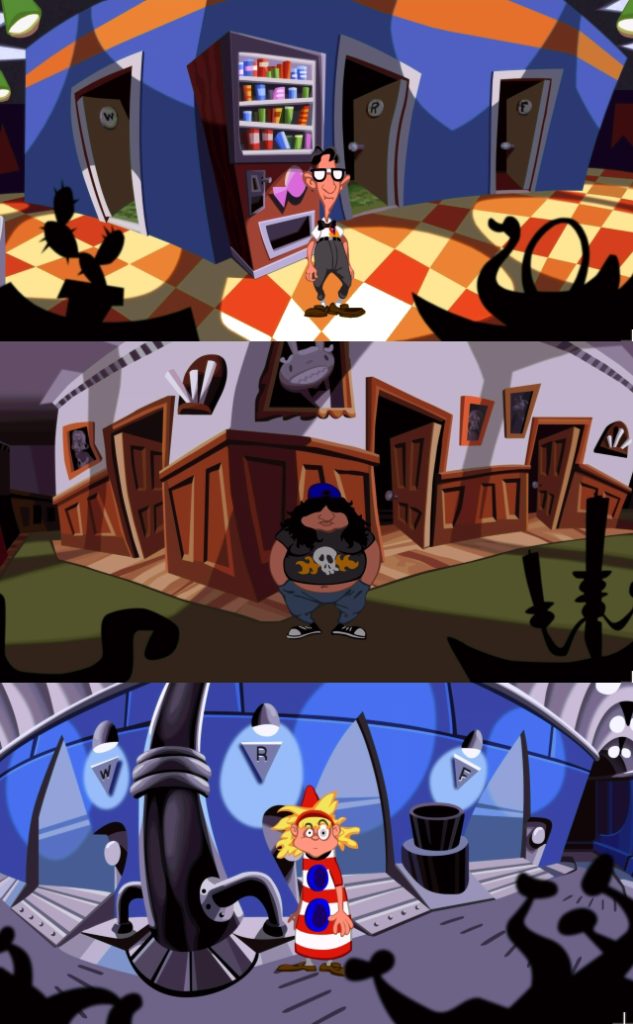

Mad scientist Dr. Fred Edison decides to send back all three of the characters you’ll control—roommates Bernard, Hoagie, and Laverne—in his three prototype Chron-o-Johns (porta-potties turned time-machines) to increase the likelihood one of them will make it to yesterday alive. Unfortunately, he uses a cheap, mail-order diamond to power his largely untested contraption and the whole shebang breaks down, sending Hoagie 200 years into the past, Laverne 200 years into the future, and Bernard neither forward nor backward in time whatsoever.

Now those last couple of paragraphs may sound a bit complicated and nutty if you’ve never played DOTT before, but this is all covered in the opening and basically takes care of all the major plot stuff for the entire game. Over roughly 10 minutes, you watch the game’s two longest cutscenes—interrupted by a tiny playable bit in-between—and then from that point on the core objectives of the game never move beyond the following:

- Get Hoagie and Laverne back to the present.

- Go back to yesterday and turn off the Sludge-O-Matic.

These objectives provide context for all of the actions your characters will perform and it’s key that the story doesn’t get built upon much beyond this initial setup. For one, it means control is rarely taken away from you in order to stuff more story down your throat. But more than that, in video games, establishing a main premise and then keeping further story elements light often results in more engaging, memorable storytelling (think of the original Half-Life and Shadow of the Colossus). This is because it is then the player’s actions that develop the narrative.

Suggesting that it is the player in charge of a story’s development in an adventure game—a notoriously linear genre—might sound like some top-tier hogwash and, yes, DOTT is a decidedly linear piece of entertainment. It is, as with most adventure games, difficult to be surprised by on a second playthrough once you already know where the story goes and how to solve all the puzzles. However, that’s true of many story-driven games; the goal is to obscure the linearity behind moments of player choice and/or by allowing the player to tackle challenges in whatever order they see fit.

DOTT goes almost exclusively with the latter route and does it masterfully. You control Bernard, Hoagie, and Laverne in the present, past, and future respectively. Each is confined to the Edison Mansion in their time period. At the start, you only have control of Bernard in the present, but he has free rein of the entire mansion, which is brimming with objects to pick up, characters to talk to, and loads of stuff to figure out. Plus, there’s only one puzzle between you and gaining access to Hoagie in the past. Once you do that, the amount of puzzling available to you effectively doubles. And after you unlock Laverne in the future, you get a good bit more puzzling on top of that. Furthermore, unlocking all the characters opens up puzzle-solving across all three eras as you can trade most inventory items between your characters by chucking them in one character’s Chron-O-John and having another fish it out of theirs. (For example, Bernard needs to pop an inflatable clown doll in the present, but has nothing pointy on hand. Laverne, however, has a scalpel.)

All this might sound overwhelming, but it’s quite the opposite. It’s aggravating enough in an adventure game to become totally stumped, but the frustration is amplified when you know there’s nothing else you can do except solve the puzzle in front of you, invariably sending you running into GameFAQs’ comforting arms. The beauty of DOTT’s approach to non-linearity (an approach admittedly already on display in Tim Schafer and Dave Grossman’s previous title, Monkey Island 2) is there are so many things to do at any given time that giving up on a puzzle doesn’t mean throwing in the towel altogether.

Taking time away from banging your head against one puzzle, you may find another you’re able to solve to make you feel good about yourself again. And in the process, you may stumble upon a new inventory item or hint that’ll help out with the puzzle that was giving you so much trouble in the first place. That it’s so rare to hit a complete dead-end makes the overall challenge seem more manageable. DOTT therefore remains engaging without ever reaching off-putting levels of stumpery.

Also awesome and of major importance is that all this puzzling is framed by the aforementioned core goals of getting everyone back to the present and then stopping Purple Tentacle yesterday. It’s important that these major story elements remain locked in place while everything else you encounter can be shuffled around. To bring up Shadow of the Colossus again, there’s really only one goal: kill all the colossi to (somehow) revive your dead girlfriend. As this objective is not altered or built upon throughout, it kind of fades into the background. I don’t know about you, but when I’m hanging onto a colossus’ butt-hair for dear life, I’m thinking about my character’s own survival, not “this is for my dead girlfriend!” And that speaks, brilliantly, to the game’s themes of selfishness.

DOTT does something similar, though it’s far less dramatic. Simply, this is a story of puzzles and so it is very much about having fun solving sequences of puzzles. You know that everything you’re doing is in service of the long-term goals of rescuing your friends and stopping Purple Tentacle, but it becomes more about the smaller obstacles in front of you. Bernard never got over his childhood fear of Oozo the inflatable clown, so you want to find a way to pop him. Hoagie needs some gold to power a super-battery and there’s a gold-plated quill Thomas Jefferson won’t let him touch. Laverne keeps getting thrown in jail so you want to find a way for her to explore freely.

It might seem an odd comparison, but in a way DOTT reminds me of the original Half-Life. The events of Half-Life are framed by a story about an alien portal and a military cover-up, but to be perfectly honest, I don’t care about any of that sci-fi nonsense (except the G-Man; he’s cool). I think Half-Life has a great story, but by that I mean the one told through my actions. In other words, to me, an excerpt from Half-Life’s story would look something like: “The door was busted so I smashed open an air vent and crawled through there. When I emerged, I was faced with an electrified pool of water, so I had to use some boxes to…”

DOTT may be about stopping a mutant tentacle from taking over the world, but it’s really about a series of contained puzzle sequences that can happen in almost any order I’d like. “I had Laverne tell the tentacle guard she had to go to the bathroom so I could send my scalpel to Bernard through the Chron-O-John. Bernard then popped Oozo the clown and grabbed his electronic voice box, which he sent to Laverne so she could…” I’m serious about this junk being memorable and satisfying. A sequence in which Bernard has to rescue Dr. Fred from being tied up in the attic and audited by the IRS to this day sticks in my mind as one of the most fun sequences in all adventure gaming—heck, in gaming, period.

Interestingly, aside from the choice of solving puzzles in whatever order you prefer, DOTT almost entirely foregoes the illusion of player autonomy. Like most Lucasarts games, you can’t get yourself killed. Further, with the exception of moments in which the narrative can be progressed regardless of which dialogue option you choose, there are no alternative solutions to any of the puzzles. This is a different approach from, for example, the early King’s Quest games which let you do things like defeat a giant either by killing him, using magic charms, or by wearing him out by having him chase you around. In Lucasarts’ own Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis as well as their Last Crusade adaptation, in nearly every encounter with a Nazi guard you have the option of outwitting, outtalking, or engaging in fisticuffs with them.

DOTT doesn’t pretend you have a choice in puzzle solutions. When George Washington’s false teeth fall out, you might happen to have two replacement sets in your inventory to give to him, but only one works (the others are too big, he explains). There are two objects (disappearing ink and a very boring book) that you can use on literally every NPC to get a reaction, but there’s only one situation in which to use either item that will actually get you anywhere.

Still, when you solve these puzzles is almost entirely up to you. This is almost the polar opposite of The Walking Dead which is predicated on the concept that the moment-to-moment choices you make are unique to each player and will result in unique outcomes, when in reality every player sees every major event play out identically but with some variations on the details. To my taste, the DOTT approach is the preferable one.

There are games better suited to greater player freedom and choice-making. I’m not personally interested in Fallout but I can understand the appeal of creating a character and completing quests using skills you’ve invested in. Sandbox stuff like Minecraft is nothing without the complete freedom it affords. But for adventure games and with linear storytelling in general, I’d rather the work not try to fool me into thinking I have freedom.

If I know there are multiple solutions to a scenario, I usually just want to see them all so I can decide which feels like the “best” one. And it’s worth noting that Sierra games (and the aforementioned Indiana Jones titles) had point systems that would award you more points depending on which puzzle solution you went with, implying that one specific solution was, in fact, “better” or more “correct.”

In other words, in adventure games, the veneer of non-linearity tends to be a thin one. If you’re trying to tell a solid story, non-linearity is overrated anyway. After all, how many Choose Your Own Adventure books have lived on as classic works of fiction?

I don’t expect an adventure game to bend to my will. I understand that I’m absorbing the story the developers have made much in the fashion they have packaged it for me. But what I do want is communication with them. I want to feel that the developers have created a world with its own rules and logic and then for them, through gameplay, to teach me those rules, so that I can get on their level.

This is how most affecting fiction works. The best novels, films, music, and games bring you into the creators’ heads and give you some insight into what’s going on in there. As opposed to feeling like you’re fighting for autonomy in a venue that doesn’t allow for it, you feel like you and the author together are sharing in their creation. In a bad adventure game, you struggle to understand what the designers were thinking. In a good one, you’re happy they’ve provided you with a roadmap through their thought process.

IT’S WEIRD BUT IT HAS SOLID INTERNAL LOGIC

King’s Quest V is one of the most unfair games ever. There’s a logic to it, but it’s designer Roberta Williams’ logic and she’s made almost no effort to clue you into how that operates. KQV is insane throughout, but contains a standout bad puzzle, quite possibly the worst, most unfair puzzle in all of adventure gaming. I’m going to detail the whole thing to you now.

At one point in KQV, your character, King Graham, enters a witch’s forest made up of several different screens to explore. After wandering around for some time, Graham discovers that the path he came in on has magically vanished, replaced by more forest.

KQV is a beautiful game, full of lovingly detailed pixel art, with the occasional extraneous background animation to liven things up. On one screen, there’s a bush in the background with some glowing, blinking eyes peeking out of it. Graham can look at, get a description of, and speak to the eyes, but to no apparent benefit. There’s no real indication that they are anything but a spooky background detail.

However, it turns out you’d be a big idiot to think that because what you’re actually supposed to do, duh, is take some honeycomb out of your inventory and squeeze it onto the path in front of you. Then you take out, double-duh, a pouch full of gems and proceed to chuck them onto the path (by clicking the gems on it three consecutive times). In this way, you learn the glowing eyes belong to a little gnome, who dashes out to steal the gems, and then gets stuck in the honey. Graham grabs him and the gnome agrees to show you the way out of the forest if you’ll let him go.

King’s Quest V (1990)

This is utterly nonsensical for so, so many reasons. As already noted, you have no real reason to believe the eyes are anything more than a background detail, let alone have any clue that they’d belong to a creature interested in gems. Second, interacting with the path upon which your character walks is a completely bizarre concept, one that simply almost never happens in adventure games ever (you cannot use the gems on the eyes; it must be on the path). Third, you can toss out the gems without ever using the honeycomb, lose them all, and be trapped in the forest. Fourth, you can enter the forest without the honeycomb in the first place and be doomed from the moment you entered.

There’s more, but you get the idea. This puzzle is so outside the realm of sense it’s maddening to try and comprehend how it was settled upon as a puzzle. There’s next to nothing on the screen in the way of hints to clue you into what to do and nothing you’ve encountered beforehand to prepare you for this moment. In fact, the game suddenly expecting you to view background details as puzzle elements contradicts what you’ve learned so far. I’m sure this garbage was logical to Roberta Williams, but from the player’s perspective, KQV is totally random.

In contrast, there are what I call “overcorrected” games like Syberia that are much easier but are also, well, boring. Frequently you know exactly what you need to complete a puzzle and just need to traipse around until you find it (e.g., you find a contraption missing a lever). This is not fun. It’s busywork. Moving even further away from puzzle-solving, we have something like Life is Strange, which basically progresses as long as you keep talking to people; it’s unclear whether the game is even interested in providing a challenge.

Ironically, these easier, more “realistic” games still suffer from KQV moments. Syberia has a bit where protagonist Kate Walker can’t get to a ladder because there are some angry birds in the way. They’re not particularly big birds; if this is supposed to realistic, why can’t she just, I don’t know, shout at them? Kick in their general direction? (The actual solution is to distract them with some grapes.) Life is Strange has an unforgivable instance of bad design in which it’s sprung on you that, throughout the entirety of an episode, you should’ve been retaining any and all information about one character in order to successfully talk her down from a building ledge. The game abruptly forces a memory-based pop quiz on you when nothing about the game had previously suggested anything like that might happen.

Life Is Strange

There seems to be a movement toward adventure gameplay that is less “weird” or “crazy,” but that’s missing the point. It’s a lot of fun to figure out weird stuff! It’s enjoyable to feel your brain bend in an odd way to reach the point where it can grasp the logic of an imagined world. An adventure game can—and, I’d argue, probably usually should—be weird. It just needs to be weird in a consistent way throughout. The world of DOTT is a weird one, but it’s one Tim Schafer and Dave Grossman want you to be able to have fun in. To that end, there are only a couple of rules and the game rarely breaks them.

One, pick up everything. Admittedly, the idea of picking up anything that’s not nailed down is an adventure game staple and there is some expectation that you’ll already be familiar with it. DOTT was originally released back when games came with physical manuals and this rule was mentioned in the manual, but there’s nowhere within the game itself you’re told “pick up everything”.

Still, the game does often at least hint that you should be snatching up whatever you can. Adventure game protagonists are basically all kleptomaniacs and DOTT takes that hilariously to heart. The characters serve the story and, to repeat, the puzzles are the story. To that end, your characters are regularly obsessed with filling their pockets with junk. Whenever you meet an NPC in possession of an item, you get a dialogue option specifically to express your interest in it (e.g., “Nice crowbar,” “Nice cigars,” “Nice teeth”). This way, even if you, the player, can’t see much use for an object, you at least have the incentive that your character wants it.

The second rule is DOTT functions on cartoon logic. The art style and general tone of the game are heavily inspired by animator Chuck Jones and the Looney Tunes universe. This is communicated through the art: the way backgrounds all look sort of bendy or in characters’ exaggerated, reaction animations (jaws dropping, eyes bugging out). Characters bend and stretch, too. Hoagie’s a very wide individual, but he can squeeze through a tiny attic window and can also shimmy down the mansion’s chimney.

The Lucasarts no-death design credo fits DOTT’s world extremely well. Laverne can get electrocuted, but—in classic cartoon fashion—when it happens you see her skeleton as she gets zapped, a little bit of smoke drifts up from her head, and then she’s fine. Bernard gets his head blown off by an explosive cigar; his head then turns to ash, disintegrates, and another head miraculously pops out from his shirt collar. He falls off the roof of the house at one point, making, naturally, a Bernard-shaped hole, but he’s A-Okay. In fact, you need to make him do this to progress in the game.

Also in the spirit of cartoonishness, many puzzles hinge upon how incredibly stupid everyone is. Distracting someone is as easy as telling them to look behind them (a trope started by Monkey Island) for any number of ridiculous reasons (“The British are coming!”). Several puzzles are based on swapping or replacing objects: some novelty chattering teeth for some false teeth, a right-handed hammer with a left-handed one, and a novelty gun for another kind of novelty gun.

Remember how Bugs Bunny always fooled Elmer Fudd by dressing up like a lady? In a similar vein, Laverne (who is trapped in a future dystopia controlled by tentacles) is considered a particularly ugly human until she puts on a tentacle costume. Even though her obviously human face is visible and she has to lift the front of the costume up to walk, thus displaying her blatantly human feet, the tentacles buy it and, hilariously, now think she’s a total babe. Later, Laverne is able to enter a mummy into a human beauty contest. The judges know it’s a mummy but they don’t care, so long as you pretty him up. The basic puzzle motto here is everyone’s dumb and nobody notices or worries much about your shenanigans. They just roll with it all.

DOTT does a good job being consistently cartoonish, but it’s not enough in an adventure game to just tell someone “it’s cartoon logic” and send them off on their merry way. Now-defunct French studio Coktel Vision’s Gobliiins series and the largely-forgotten The Bizarre Adventures of Woodruff and the Schnibble of Azimuth function on some manner of cartoon logic but you may have to be an actual cartoon (or at least French) to get through them without a walkthrough as your constant companion. For an adventure game to be challenging but not impossible, you need to stuff it full of hints.

HINTS ARE EVERYWHERE

The adventure game genre has quite the legacy of terrible garbage puzzles and the reason they fail so badly can be traced almost entirely back to signposting, the fine art of subtly pointing the player in the right direction. If a game is too obvious, too afraid of the player getting lost, it feels like the designer is breathing down your neck, telling you what to do at every turn. If not enough direction is given, you’re left unequipped to fend for yourself in an alien environment. In either case, the end result is the sense that this story was not made for you. This is the developer’s world and it is for them to enjoy it or to tell you exactly how it is to be enjoyed. And getting this sort of sense from a game is a one-way ticket to breaking your immersion.

DOTT has zany puzzles with ridiculous solutions, but the game is absolutely packed with hints and nudges, resulting in unobvious, yet rarely unfair, puzzle solutions. I am honestly unsure there are any other adventure games out there, period, that so constantly prod the player in the right direction without it ever feeling like you’re being told exactly what to do.

Recall that KQV puzzle, which has no hints that there’s a gnome you need to catch with some gems and honey, unless you count those glowing background eyes (I don’t). That’s an abnormally bad puzzle, but, honestly, being given little to no indication of what you need to do in a situation is not uncommon to the genre. Lucasarts’ own Sam & Max Hit the Road, The Dig, and unfortunately, even Tim Schafer’s follow-ups, Full Throttle and Grim Fandango have multiple sequences that aren’t challenging, but rather, straight-up confusing (I solved the roulette puzzle in Grim without ever fully understanding what I was doing).

The main reason DOTT excels at signposting is that it layers its hints. You’re usually given multiple motivations and clues to solve every puzzle sequence (quite an improvement over being told nothing). For example, in the past, Hoagie enters a room to find the founding fathers—John Hancock, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington—attempting to draft the Constitution. The first clear thing is that Hancock is hunched up and shivering. If you talk to him, he tells you that Jefferson refuses to build a fire, but he might if Washington was cold too. Talking to Jefferson confirms this.

Why would you want to start a fire though? Well, truly, in DOTT the ends justify the means. Recall the Syberia puzzle I mentioned in which you already know what you need to do but you need to find the thing that lets you do it? DOTT is typically the opposite: you know there’s something you can do, but not yet how to do it or possibly even why. You solve puzzles purely to make something happen and see what opportunities then open up for you.

That said, you do usually have some motivation to complete the puzzle in front of you (although it may be unclear how it will help with the ultimate goal of stopping Purple Tentacle). In this case you have, one, the simple fact that John Hancock is cold and maybe you want to help the guy out. If that doesn’t float your boat, there’s also your character’s eternal desire to pick stuff up; Hancock is wrapped up in a tacky blanket and one of the dialogue options when you talk to him is “Awesome blanket there, dude.” So now you have some idea that Hoagie wants the blanket and, if the room were warmer, you’d maybe be able to get it from Hancock.

Objects in the environment give you more incentive. There’s a canary in a cage above the fireplace. There’s a lever inside the cage that connects to a bell. If you mouse over this canary contraption, the game calls it a “smoke detector.” This is plenty clear already, but, if you need further confirmation of the canary’s function, you can ask the founding fathers about it. Again the question becomes why would you want to set the canary smoke alarm off? You may have no idea. But the possibility that you almost certainly can gets you thinking about it.

In actuality, the reason you want to do all these things is the gold-plated quill pen in the room that Thomas Jefferson won’t let you touch and, as you learn from Dr. Fred’s inventor ancestor, Red Edison, gold is one of the ingredients he needs to create a super-battery that can power Hoagie’s time machine and send him home. However, it’s very possible you won’t make the correlation that starting a fire and setting off the smoke alarm will get you the quill. You don’t have any real idea what will happen once you set off the smoke alarm. But you have enough incentives here to want to try it and see where it gets you.

Incidentally, I haven’t even detailed the other puzzles that tie into this one, like how exactly you’re supposed to make George Washington cold. Like so many of the puzzles in DOTT, it comes down to an indirect solution: you might not literally be able to make Washington cold, but maybe you can make him look cold. And there are hints about this too: Hancock’s shivering animation includes chattering teeth and George’s idle animation shows him occasionally removing his false teeth (and you can ask him about them, too). And, by the way, lest this sound too straightforward to you, know that simply starting the fire does not set off the smoke alarm. You have to do something else after that. All of DOTT is about awesomely stringing together hints and puzzles into satisfying sequences.

The game also mostly does a good job of making certain you don’t miss information. There’s a chance of the player completely missing an important conversation about Dr. Fred and his office safe, so the same clues are repeated by Nurse Edna. Also, though you can exhaust most of the dialogue with NPCs pretty quickly, if you speak to them again, they usually repeat the main hints you need from them (though occasionally they don’t, probably DOTT’s biggest failing).

Finally, one of the most amazing aspects of DOTT is it has an in-game hint system, but you’re not expressly told it’s there. It’s not, as I’ve seen in a number of classic adventure game rereleases, something like a question mark icon in the corner of the screen that you click on to get hints. Or like the hint system in Machinarium, which requires you to beat an action mini-game to unlock a comic that displays exactly what you need to do. The problem with these hint systems is they feel separate from the game’s world, like a slightly less-removed GameFAQs. Furthermore, they still make you feel like you’ve given up and resorted to cheating.

DOTT’s hint system comes in the form of Dead Cousin Ted, a relative of the Edisons who is dead, mummified, and present in all three time periods. Your characters can (but never have to) have conversations with Ted, though he never talks back. Much of the dialogue is just for laughs (e.g., Hoagie can carry on a lengthy monologue about his friend’s metal band), but it’s also almost always possible to talk to Ted about your current conundrums. This is never too specific—you can’t, for example, discuss getting Hancock’s blanket away from him—but you can discuss bigger goals like how to get the items for Hoagie’s super-battery, how Laverne might win the human beauty contest, or how Bernard can save Dr. Fred from the IRS agents.

You’re never told a full solution; if anything you’re just reminded of your objectives and possibly put on the right track to solve them. I say “possibly” because, based on the dialogue options you choose, you may veer off into complete nonsense (metal bands, etc.), rather than getting anything useful. Also cool is that sometimes the hints you get with one character are applicable to another. Laverne can say to Ted: “I’ve got to get power to my Chron-O-John. I guess I could wait for a lightning storm,” which is actually an indirect hint for Hoagie. (A hint in one time period that’s useful in a different one is another extremely clever tactic DOTT pulls repeatedly.)

The original Simon the Sorcerer had a similar in-game hint system: a senile owl who would blather a lot of nonsense with the occasional actual helpful hint mixed in. The subtle, but utterly brilliant, distinction with Dead Cousin Ted is that you aren’t really talking to anyone. Your character is really just having a conversation with him or herself and you’re picking the dialogue options. You are not being passively fed hints. Just as you learn stuff by digging through dialogue trees with NPCs, here you are investigating your avatar’s thoughts to reach potential clues. In this way, even the in-game hint system feels driven by and inclusive of the player.

YOUR TIME IS NOT WASTED

Besides wonky puzzles, something that also makes adventure games hard to love is how passive they are. A major draw of the genre is its accessibility to players of all skill levels, as the challenge is taxing on the brain and not the reflexes. But I can’t help but notice that, in many point-and-click games, it’s really point and click and then wait for your character to lope across the screen. I have played a lot of adventure games and over time I’ve become bored. I have an urge to be more directly involved with the action even though I know it’s not that kind of game.

Later adventure games addressed this by adding niceties like the ability to make your character run (The Longest Journey) or letting you double-click on screen exits to jump to the next location (The Curse of Monkey Island). But these solutions don’t quite get to the heart of the problem. When you’re stumped, invariably you’ll end up backtracking through all the locations you’ve already been to, looking for anything you may have missed. If your character runs instead of walks, it’s perhaps half as boring, but it’s still boring. And, this may just be me, but, though I appreciate and obviously utilize it, the ability to click through locations without my character manually traversing them somewhat removes the feeling of it being an adventure and turns it into a slideshow.

Of course many current games, being in 3D, now put you in direct (typically controller or keyboard) control of the character so you’re a more active participant in their actions. But the nature of the genre still tends to involve a fair amount of tedious meandering about. The Walking Dead avoids this sort of thing, but does so by sacrificing puzzles in service of action sequences and quick time events, thereby losing some of the accessibility that makes the genre so appealing in the first place (this does, in an odd way, echo the old Sierra games, but, as I’ve said before, the action in those was a misfire).

The incredible thing about DOTT is it sticks to being a tried-and-true point-and-click game and yet you almost never feel like you’re just observing your characters wandering around from place to place. It does this not by making tweaks to the way you control the character, but rather by having an environment with a design conducive to the gameplay. Very simply, DOTT takes place in a house. This is not an adventure across vast valleys and deserts; it’s a bunch of hallways and rooms. All the locations are fairly compact, so moving between them is a brisk and easy process.

Even more ingenious, the house is a (sort-of) loop. There are few dead ends and when you get to the top of the house, you don’t have to go all the way back down as Bernard and Hoagie are able to climb down the chimney and end up instantly back on the first floor (and they can scramble back up the chimney just as quickly). This might sound nigh-irrelevant but I can’t really stress enough how useful this is in a genre so dependent on backtracking. In truth, considering DOTT takes place entirely in a confined space of finite locations, one could argue the entire game is backtracking, yet this one smart little environmental design inclusion makes it so you never think about it like that at all.1

Admittedly, in Laverne’s time, this loop doesn’t exist and there are more dead-ends overall. However, the aforementioned compact nature of the setting and the individual rooms still make the experience generally breezy. Plus, Laverne’s time being more restrictive does work well thematically. Laverne happens to be in a future in which tentacles rule the world and she’s an escaped prisoner, so it only makes sense she’s not able to roam as freely as Hoagie and Bernard in the past and present.

Speaking of which, having the game take place in the same location in three different time periods is another stroke of design genius. As explained before, games that only let you explore a few locations at a time can feel limited, frustrating the player more readily when they get stuck. Games like this also don’t allow for nearly as much opportunity for the player to choose what order they wish to solve puzzles in. However, presenting the player with an abundance of locations can be overwhelming and makes it easy to get lost (e.g., recent game Dropsy, which is quite fun, but also a bit daunting).

DOTT lands upon the perfect marriage of these design styles. It’s a confined area, but it’s one that repeats three times. The mansion does have quite a lot of rooms and since you’re encountering them all thrice over, the game ultimately has quite a few screens to explore. But having the same layout in all three time periods breeds familiarity, so you’re never lost and it never feels like there’s too much to tackle. At the same time, the art you see, the characters you run into, and the obstacles you’ll face in each period vary wildly, so exploring never feels repetitive or limited.

Sure, I don’t know that every game could pull off this kind of environment. I mean, sometimes you want a game about an epic adventure over great fields and valleys. But DOTT is an amazing example of the environment being simultaneously in service of the gameplay and the story.

In terms of the story, cutscenes are very rare. This is a genre with a major info-dumping problem, usually employing lengthy cutscenes that develop story at key moments. But, again, the core objectives in DOTT never change, so there’s no need to interrupt your playing with non-interactive movies. There are little interstitials that pop up occasionally between room transitions (e.g., newspaper headlines updating you on Purple Tentacle’s world-taking-over progress), but these are short, funny, and sometimes also serve as little reminders of what puzzles still need solving. There are only a few longer cutscenes and they show up upon completion of certain puzzle sequences. Chaos is the end result of many of your actions and getting to watch it play out through the awesome, cartoony animation means this is one of the rare cases in gaming where, when a cutscene shows up, it’s actually a treat.

THE PLOT IS SPARSE BUT STILL HAS ITS CHARMS

Most of them are extremely flawed, but adventure games remain my favorite genre because they often do better jobs of storytelling and establishing tone than video games typically manage. And I have to acknowledge that on this front, there are a lot of games that beat DOTT out. Sanitarium is a lesser-known game with some absolutely atrocious puzzles, bad voice acting, and super out-of-place action sequences. But the story is surprisingly well-paced and knows not to screw up its narrative twists and turns by showing all its cards at once. Tim Schafer’s follow-up to DOTT, Full Throttle, is one of my all-time favorite games for its compact, unique story as well as its amazingly cinematic presentation. Unfortunately, design-wise, it’s a pretty bad game with a lot of set pieces that are cool but all have dissimilar, poorly-communicated rules. I still love it though, and it’s also getting a remaster, so I’d recommend checking it out.

DOTT’s story doesn’t stick with you in the same way as one of these games, basically because of everything I’ve described up until this point. It is such a gameplay-focused, madcap puzzle free-for-all that the story takes a bit of a backseat. But although the story is on the lighter side, it would be a disservice to suggest that what’s there is without charm.

First and foremost, it’s a comedy and it is pretty funny. A nice feature of so many Lucasarts adventure games is that you can have your characters be total nuisances; it’s fun using the boring book and the disappearing ink on NPCs and ticking them off. Some of the cartoonish sight gags—like all the stuff in the Dr. Fred IRS rescue—are good fun. There are gems sprinkled throughout the dialogue, like when Bernard tries to get Dr. Fred to sign a contract by saying, “Sign it or I’ll… get real mad.” “And do what?” retorts Dr. Fred, “Not be my friend anymore?” Plus, there’s a part you kick an old lady through a doorway, never to be seen again.

It also shouldn’t be overlooked just how unique the protagonists of this game are. As they’re largely vessels for jokes and puzzles, they’re drawn a bit thinly, but just that this game stars three roommates—a nerd, a metal head, and a med student—is decidedly weird and exceptionally unique. In a medium largely populated by angry, muscley guys, it’s so rare to have lead characters who look like this. Bernard has just terrible posture. I don’t think Laverne gets nearly enough credit for being a truly odd, yet cool and completely nonsexualized female game character. And Hoagie is just so wide.

The fact that this is a story of time travel enriches the plot so much as well. There are just so many charming, brilliant concepts, like stuffing a hamster in a freezer to keep him alive for use in a puzzle 200 years in the future. Or the notion of placing some wine in a time capsule in the 1700s so that you can plunder said capsule in the 2100s, and then send the wine, now turned into vinegar, back through time to the 1700s again. It’s also funny that many of the character models (and sometimes voice actors) from time period to time period remain the same, implying you’re meeting ancestors and descendants. It’s an incredibly tragicomedic notion that George Washington’s distant future descendant is a guy named Harold whose claim to fame is being the prettiest boy in a human beauty contest judged by evil mutant tentacles.

It’s also a lot of fun that most everything you do results in chaos. To refer back to how DOTT makes the player feel like they are the one affecting the narrative, the game does an amazing job of showing you that the stupid little actions you performed just because you wanted to pick up a blanket have far-reaching consequences. You give a failed, suicidal inventor false hope just to get him out of his room so you can steal his stuff. Harold—who has nothing but his status as a pretty human—is disqualified from the human beauty pageant because of your actions.

The game’s playful approach to time-travel allows you to screw with the past and future with hasty abandon, giving the story a much grander feel. Even though you’re stuck in a house for the entirety of the game, you are effecting universal chaos that will ripple throughout time. I won’t spoil it here but the absolute last image in the game is a truly joyous surprise demonstrating that, what to you was just one puzzle to be solved, had lasting ramifications for all humanity.

Also, the final confrontation with Purple Tentacle is one of the better endings in all adventure gaming. As adventure games are not heavily action or reflex-based and as many now follow Lucasarts’ no-dying example, they struggle to come up with a way to create rising tension and successfully climactic “boss fights.”

Sierra games, in their final sections, ramp up the chance of dying (which is saying something). This ends up being antithetical to rising tension when you have to repeatedly save and then load after each death. Full Throttle is a mostly no-death game that couldn’t figure out how to make the ending feel dramatic without suddenly introducing dying in the final sequence, rewinding the scene for you each time so you can try again. This, too, also pretty much kills the tension. DOTT is never a particularly intense game, so the ending remembers to keep it light-hearted, with a tiny, but nonfatal consequence for screwing up, and puzzle sequences that are challenging enough to not feel throwaway, but that aren’t too complex either. This way you’re still solving puzzles as usual, but also enjoying the momentum of your victory lap to the final cutscene.

OH YEAH, THE PRESENTATION

This has been an analysis of DOTT in terms of gameplay design, so I didn’t spend loads of time on how the game looks or sounds. Still, it’s certainly worth a quick mention that the goofy music—though not something I listen to outside of the game like some of the gorgeous stuff from the Monkey Island series—is burned onto my brain all the same and absolutely fits the cartoonish vibe. DOTT is of an era where voice acting in gaming was still kind of being felt out so the delivery is questionable here and there. But in general the voice work is great, especially considering it was only released three years after stuff like King’s Quest V.

I’ve touched on how the cartoony art complements the cartoony logic, but it was also one of the first strikingly unique art styles in a Lucasarts game. The odd, bendy look to the environments gives them the appearance of being shot through a fisheye lens and it simply looks like nothing else in gaming. Or at least it didn’t before loads of gamers who played this game jacked the style. Here’s just a short list of games that take clear inspiration from DOTT: Ben There, Dan That and its sequel Time Gentlemen, Please! (both quite good adventure games), Bud Tucker in Double Trouble (possibly the worst adventure game I’ve ever played), Hector: Badge of Carnage, Tony Tough and the Night of Roasted Moths (it’s terrible; don’t play it), The Great Fusion, Orion Burger, and James Peris. And beyond that there are loads of free Adventure Game Studio titles like No-Action Jackson, Apprentice, Dr. Lutz and the Time Travel Machine, Murder in a Wheel, Once Upon a Crime, and Professor Neely and the Death Ray of Doom.

Hell, some years back I tried to make an adventure game with a couple of guys and the artist, given no particular direction and left to his own devices, made everything look like DOTT. Clearly, the style grabbed hold of many a gamer’s brain and stuck there. It’s too bad more developers haven’t cribbed as heavily from the puzzle design.

OKAY, I’M DONE

Day of the Tentacle is not perfect. There are a few puzzles that don’t fit with the otherwise cartoon logic. The aforementioned wine-to-vinegar puzzle, for example, though a great use of time-travel, requires some real-world reasoning. Another puzzle that’s always stuck in my craw as feeling too real-lifeish is when you have to enter a room and close the door to find a ring of keys hanging on the doorknob. You get a crowbar and a hammer and there are some puzzles where it feels like either should work but, for no good reason, only one does. There are also a couple of instances of pixel-hunting, where you have to slowly scan all over the screen with your cursor to find hard-to-see interactable objects (though the remastered version rectifies this with a button that highlights every object you can interact with). As previously mentioned, there are places you are unable to re-hear important hints.

I’ve also been tiptoeing around the fact that there’s a fair amount of picking conversation options and sitting through dialogue. In fact, Tim Schafer did a Let’s Play of DOTT some time back, during which he made note of it being a tad dialogue-heavy. However, I will say that at least the majority of the dialogue serves the double purpose of being funny and providing hints and objectives. Furthermore, owing to the finite nature of the game’s setting, it doesn’t take all that long to chat with every character, leaving you free to do all the other puzzling. But still, yes, it’s a bit chatty, though nowhere near the degree of a Broken Sword, The Longest Journey, or The Curse of Monkey Island (still all great games, by the way).

Mostly, however, Day of the Tentacle has a great feeling of forward momentum with challenge that keeps you engaged but doesn’t put you off. It’s astounding just how much of it—from the art, to the setting, to the restrained storyline—is all in service of keeping the puzzles logical and interesting. It’s even more amazing when you consider it came out in 1993 and so few adventure games have been able to come close to its level.

Even Tim Schafer’s own follow-ups, Full Throttle, Grim Fandango, and Broken Age—though they have undeniable charms of their own—suffer from moments of obtuse puzzling and disappointing design (this awesome, informative video by Mark Brown touches on some of this). It’s just so strange that a game from the early nineties got so much right and, decades later, it seems few developers look to it for inspiration (though if I were going to name games that did a pretty good job, Ben There, Dan That and Time Gentlemen, Please! are good contenders, as well as the utterly gorgeous The Curse of Monkey Island, which isn’t quite as refined as DOTT but is definitely still one of the most accessible adventure games ever).

In a period of adventure games being ever-streamlined, favoring story over gameplay, I’m glad Day of the Tentacle is back to show us how it’s done. It’s a game that recognizes how story and gameplay must be one and the same for puzzle-solving to involve the player. It’s a game that brings you into its zany world and gives you the tools to get your brain on its wavelength. Oh, and it’s a sequel to Maniac Mansion, something I haven’t even bothered to mention because this game stands on its own and is so much better than its predecessor.2

The first time I played Day of the Tentacle, I played it with my sister. We had been stumped on a puzzle for a while: we knew Laverne needed a tentacle costume but had no idea where to get one. Our parents called us to dinner so we had to stop playing, but, as we ate, we sat quietly, mulling over the puzzle.

After a few minutes, my sister suddenly shouted, “Betsy Ross! Betsy Ross said ‘put the pattern on the table!’”

“Oh, yeah!” I said, excited because I realized we had exactly what we needed to solve the puzzle.

After dinner, we tried it and it worked. And it felt great. Because we understood the game.

Day of the Tentacle is the best-designed adventure game ever. And we can learn a lot from it.

1. An integral mechanic of the game is transferring stuff between characters through time by flushing inventory items down their Chron-o-Johns. One way to do this is to schlep your character over to the Chron-O-John, place an object inside, switch to another character, walk them over to their Chron-O-John, and have them retrieve the object. However, you can also simply select an item in your inventory, drag it over a character’s portrait, click, and send it instantly that way.

This latter, far speedier method is, sadly, only explained in the physical manual included in the game’s original release. I’ve discovered recently that many people who played this game back in 1993 never read the manual and had no idea this was possible, adding a lot more tedious backtracking to their time with DOTT.

I tweeted at Tim Schafer that, since so few people are aware of this incredibly useful and timesaving mechanic, Double Fine should consider patching the game to include a mention of it somewhere. I guess such a patch is not currently planned as Tim replied, “Tell everyone you know!” This footnote is me doing my due diligence to honor that request.

2. If you’re truly worried about being confused in Day of the Tentacle because you haven’t played Maniac Mansion, be aware that the full original Maniac Mansion can be accessed and played inside of DOTT itself (and, yes, it is also included in the remastered version).

Amen to that! Finally, I now have this post to direct people to when I’m arguing why DOTT has been the best video game ever and why millennials should play it before spending their money on new so-called AAA games, which will be quickly forgotten in a month or two. Not to mention that DOTT also teaches kids some history in an amusing way. E-X-C-E-L-L-E-N-T post, Joe!

Thank you very much! I’m glad you enjoyed it. I appreciate you sharing it around.

Pingback: Analysis of Day of the Tentacle – Point n' Click Adventure Game Research Blog